Vendors design complex channel frameworks to mitigate risk, but this unnecessary complexity often hinders partner engagement when simplicity would be far more effective.

If you’ve ever explored sports betting apps like FanDuel or DraftKings, you know you can wager on wins versus losses, victories that beat the spread, and even how well individual players perform.

Some of these apps also allow for more elaborate and esoteric bets requiring a series of events for a payout. For example, the Lakers must win by 7 points, LeBron James must hit 10 three-point shots before the end of the third quarter, the Bucs must miss 5 rebounds in the fourth quarter, and a 10-year-old named Ted sitting in the third row must spill his popcorn in the second quarter and cry so loudly that the game stops for 3 minutes and 10 seconds.

Sounds impossible, right? That’s largely because it is — by design. These bets are called parlays. They offer big odds that result in big payouts, making them irresistibly attractive to high-stakes gamblers. Betting apps love them because they rarely pay out. For casinos or bookies, these bets are incredibly profitable.

Parlays work so well in favor of sportsbooks because they’re built on a simple principle: The more things that must happen, the more unlikely they are to happen. This paradigm is formally known as the Law of Compound Return Risk, which states that the more steps or parties involved in a process, the greater the risk of delay, misalignment, or failure.

Channel programs are often subject to these same concepts. In vendor organizations, everyone from the C-suite to the sales floor knows they can’t cover the total addressable market without the cooperation and support of partners. Partners economically extend the capabilities and capacities of vendors’ go-to-market models and operations.

Vendors craft channel programs to provide scale, uniformity, and manageability to their partner relationships. Instead of managing thousands of bespoke agreements and relationships, vendors corral partners into frameworks under which most operate under relatively similar conditions.

Channel programs provide efficiency while simultaneously reducing vendors’ risk exposure. By bringing all partners under one tent, vendors can more effectively allocate resources to achieve success in their indirect routes to market.

However, that’s often not enough for most vendors. Channel programs are frequently designed like casino rules — or parlay betting in more difficult cases. The requirements, rewards (incentives and benefits), and access to resources are predicated on partners not just doing one thing but achieving a series of objectives.

Take, for instance, a standard tier-based channel program. Partners earn higher status and more benefits by rising through the tiers in a meritocratic process. The better a partner performs, the more it receives from the vendor. At Channelnomics, we call this the system of “gives-to-gets.” It makes perfect sense to ensure that the vendor spends only the right amount to support a partner while receiving proportional returns on its channel investments.

But vendors are often more critical and cynical than that. There’s a persistent doubt in the vendor community that partners are doing enough to earn their rewards. It’s not enough for a partner to generate $1 million in sales because vendors often feel they don’t “really know if the partner did anything to earn the sale or the level of rewards that came with it.”

Channel programs are often designed like parlay bets. To earn status and receive rewards, a partner must achieve a minimum annual revenue level, maintain a certain level of technical and sales certifications, file and adhere to a business plan with revenue objectives, conduct quarterly marketing campaigns, generate a prescribed number of net-new accounts, manage a minimum renewal rate, handle Level 1 and Level 2 technical support for customers, submit copious amounts of point-of-sale data, and — just for good measure — perform rain dances during the dry season.

Simple, right?

Add to that the complexity of doing business with a vendor. The technology industry touts the benefits of data management and process automation, but most vendors are terrible at them. At a time when everyone is chasing the “Amazon Experience,” many vendors can’t generate quotes or provide order status updates to partners quickly. While vendors invest heavily in things like partner relationship management (PRM) platforms, they often struggle to process deal registrations, requests for market development funds (MDF), and earned rebates.

For some vendors, the complexity of channel programs and shortcomings of systems are features, not flaws. They believe that introducing complexity minimizes their risk of being played, abused, or taken advantage of. They add more layers of complexity, thinking they’re creating incentives for partner performance when they’re actually setting up partners to fail — or not even try.

From a partner’s perspective, why bother when the system feels rigged against you?

This seemingly insurmountable set of conditions leads many would-be or low-performing partners to seek easier alternatives. Channelnomics research on channel performance consistently finds that partners gravitate toward less profitable vendors that are easier to work with rather than more profitable vendors deemed too difficult.

The more conditions a vendor imposes on partners, the less likely partners are to engage because they know how difficult it'll be to succeed. Partners frequently push back on vendors for setting the bar too high on rebate programs, for example. Many of those initiatives have prerequisites that limit the number of eligible partners, thus reducing vendors’ expense exposure. These programs then set high goals, making it difficult for partners to achieve them without substantial investments and resource diversion. For many partners, a cost-benefit analysis shows that the benefit isn't worth their effort.

Having guardrails and standards in partner programs isn’t inherently bad. Vendors need to set conditions to ensure that they have qualified, engaged, and productive partners in their ecosystems. However, vendors must balance the level of investment partners must make to participate and the rewards for active participation.

Vendors should always strive to make their programs not just simple but logical. They must balance requirements with mutually equitable returns on investment for themselves and their partners. Additionally, they must create systems that streamline a bidirectional information flow with partners.

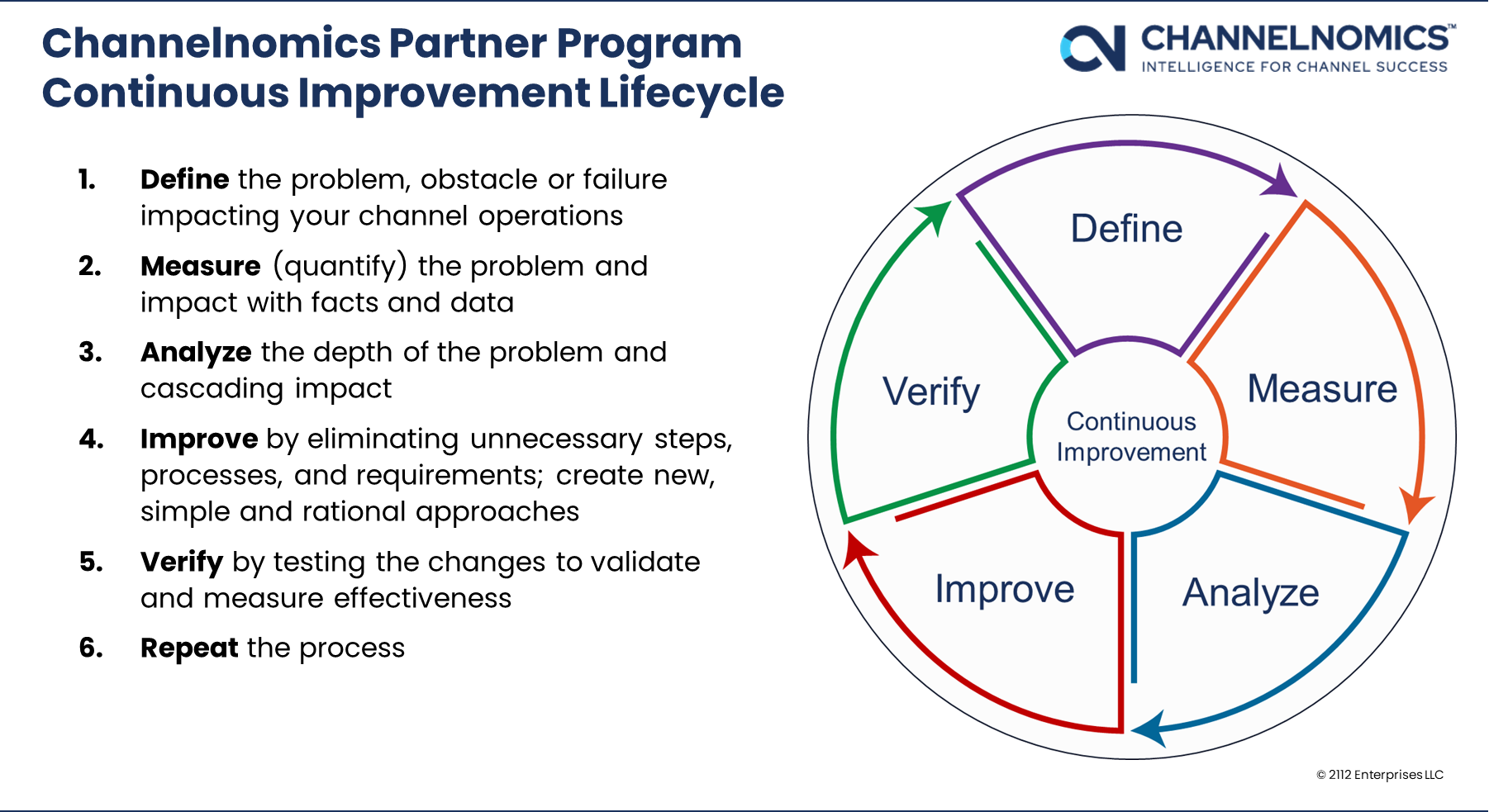

Channelnomics recommends a process of continuous improvement, in which partner program managers engage in periodic evaluation of their program structures and performance, actively look for ways to reduce complexity, test the results, and repeat the process.

Click here to download a copy of the Continue Improvement Lifecycle slide.

Vendors that focus on simplicity and continuous improvement tend to achieve higher levels of partner participation and indirect sales growth.

As Steve Jobs famously said, “Simple is hard.” It is — and it doesn’t happen quickly. Channelnomics can help by assessing channel program complexity, identifying bottlenecks, and prescribing processes for continuous improvement. For more information about how Channelnomics can help streamline your partner program, contact us at info@channelnomics.com.

Larry Walsh is the CEO, chief analyst, and founder of Channelnomics. He’s an expert on the development and execution of channel programs, disruptive sales models, and growth strategies for companies worldwide.